|

A COMPARISON OF MONTESSORI

|

—Susan Mayclin Stephenson, |

|---|

A version of this article was published in 2012 issue of Communications, the Journal of the Association Montessori Internationale (AMI) |

For video clip examples of age 0-1, 1-2, 2-3-year child development to go; 0-3 Video clips |

The Joyful Child: Montessori, Global Wisdom for Birth to Three, with an introduction by Dr. Silvana Montanaro, founding international director of the AMI Assistants to Infancy course. Also there are links to some of the translations can be found here: Book and Translations |

|

In 2006 and 2008, as a guest of the Bhutanese government and friends, I began to research Bhutanese family life and culture in preparation for Montessori education in Bhutan. This article highlights some of the similarities and differences between traditional practices in Bhutan and the Montessori Assistants to Infancy (A to I), birth to three, training that began in Rome in 1947. Resa Lhadon, who I visited at age 8 months and again at 20 months, will provide us with examples. She lives in the traditional family farmhouse in the Paro Valley with her parents, sister, and at times grandparents and other members of the extended family. But first I would like to share with you a personal experience, an epiphany, which began my own journey of studying the first three years of life. AQUARIUM EPIPHANYMy daughter and I sat watching a slide presentation at the NAMTA (North American Montessori Teachers Association) Birth to Three Conference in Annapolis, Maryland in 1985. A little blond, curly-haired boy, almost two years old, was standing on tiptoes leaning against a very large aquarium filled almost to the top with water and fish. He was dressed in short white cotton pants, a white shirt, and an apron that covered the top half of his torso. He supported his leaning body by holding on to the top of the large aquarium with his left hand, and with his right reached far into the water, a bright orange pitcher held in this hand visible through the glass. My initial reaction, and probably that of other experienced 3-12 Montessori teachers in the audience, was that this was going to be an example of what to do when a child was attempting something for which he was not yet old enough. The second slide showed the same youngster pouring water from the orange picture into a bucket next to the low table holding the aquarium. There was a look of intense concentration on his face that made it clear that he was exerting great care and effort in pouring the water slowly, spilling as little as possible on the floor. There were no adults in sight. In the third slide he was emptying the large bucket into a low sink, and holding the bucket securely with both hands in such a way that the lip of the bucket was directly over the middle of the sink to avoid spilling. And in the last picture this young worker was using a cotton floor mop with a handle about two feet long, to clean up spills around the floor mat. Judi Orion, the Montessori A to I teacher trainer who was showing us scenes from the Montessori Infant Community for children from 1-3 at Post Oak Montessori school in Houston, explained that the child had gone on to almost empty the aquarium, leaving just enough water for the fish. Then he had wiped clean the sides of the aquarium, inside and out, and carefully filled the tank with fresh water. This was the logical cycle of work he had been taught, and it took a period of concentration more than an hour to complete. The silence of the audience was profound. Until that moment I though that I had done a pretty good job teaching children from 3-12 in a way that respected their abilities, their physical and mental potential, and supported their independent action and thinking. But I would not have presented this aquarium-cleaning activity until a child was five or six years old! I would have limited lessons for a two-year-old to safely pouring rice or water back and forth between two small pitchers, or perhaps dusting a bookcase or laying out matching vocabulary cards. To myself I said, “I have been treating my Montessori children like babies!” This experience turned my life around. After 15 years of teaching I started over. I took the Assistants to Infancy course with Ms. Orion and Dr. Montanaro in Denver, and have continued since then to try to learn everything I can about the first three years of life, and to share as I learn. Below is one such exploration.

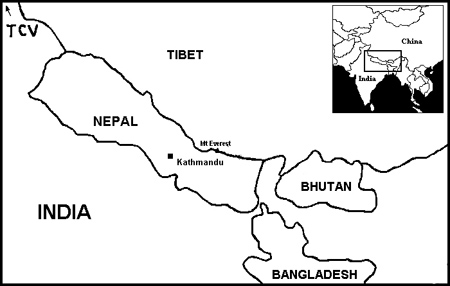

BHUTANFor 100 years a king who considers GNH, “Gross National Happiness,” rather than GNP, “Gross National Product,” the most important measure of the success of the nation, has led Bhutan. Everywhere one travels in this country Buddhist influences are obvious: protection of the environment, worship, generosity and kindness toward each other. Each day begins with a prayer “for the happiness of all beings.” All produce is organically grown, not because this is a popular new movement, but because it is against the religion to kill, even to kill insects. In the past there were four Tibetan Buddhist kingdoms where one could observe a culture like this: Tibet, Sikkim, Ladakh, and Bhutan. Today Bhutan is the only one that has not been taken over by another country, which is one of the reasons I am interested in not only introducing the best of Montessori, but in being instrumental in preserving the existing precious culture. Bhutan, like Nepal, has only been open to the West since the 1960s. Before that time there were not even any roads in and out of the country, no schools except in the monasteries, and no postal system. Bhutan is half the size of Indiana, and due to good advice the Bhutanese are doing a very good job of protecting this tiny country from ravages of unplanned development and tourism that have destroyed so much of Nepal. Montessori, if introduced with sensitivity to the culture, will be very helpful to the development of the country, and perhaps we can all learn something in the process.

THE FIRST YEAR OF LIFE1 - THE PSYCHOLOGICAL LEGS A healthy emotional foundation, if supported in the first year of life, can sustain a person for a lifetime. The child stands tall, in a manner of speaking, when he stands on two strong “psychological legs.” The World as a Safe Place: The first “leg” has to do with a child’s world view, his feelings of security as a member of a family and a culture. It is an attitude that the world is a good place, a safe place. The way we give this support to the child is in caring for him during pregnancy and birth, and in the first days and weeks of life: providing a strong family bonding experience, responding quickly and gently to his requests for care and feeding, and with gentle handling and speech. Self-respect and Self-love: The second “leg” is an attitude toward oneself: it is the ability to love oneself just as one is, without having to change or become better to deserve love. Such a healthy attitude of self worth is fostered by respecting the child’s natural instincts of when to eat and sleep, and how much. And it is fostered through respect for each child’s individual timetable in learning to talk and walk. It means we do not rush a child. Instead we create an environment that provides the tools, such as a mattress on the floor that the child can get in and out of on his own, and a bar or stool or special wagon that he can use at any time to practicing pulling up or walking. This “leg” is developed basically in the first year of life. I am sure we all know adults who are trying to rebuild these attitudes of trust and self-love in themselves. It is clear that babies are born with them. It is up to us to create an environment that protects them from birth. 2 – PRENATAL MONTHS AND BIRTH A to I: The Assistants to Infancy (A to I) course begins with the study of conception and pregnancy, to make us aware of the fact that this is where the life of a child begins. A gentle birth is considered optimum. During the A to I teacher training course, some trainees take the additional training in R.A.T, or Respiratory Autogenic Training. R.A.T. has been used for years in Europe to teach a mother how to completely relax between contractions during birth, helping to create an easier, faster, birth that is better and safer for mother and baby. All students in the Denver Montessori A to I course, for example, practice it daily during the 2 summers. Those taking the further training learn to teach this skill to women or couples during pregnancy. I observed two such births in Rome during my training and was astonished at the ease of the childbirth experience of two primiparas (women giving birth for the first time). Bhutan: Resa was considered a year old when she was born. For purposes of an interview it is often difficult to establish a child’s age because most births occur at home, the date not recorded. Birthdays are not an important part of the culture. During the prenatal months a child is considered an already existing new member of the family—usually an extended family that includes 3 generations living in the same home. In traditional home births in Bhutan, the position of the mother is on her hands and knees, actively involved with the delivery, but Resa was born in a hospital, with the mother lying on her back, unable to be as active in the delivery. Beginning at age 18, imitating her own mother, and all during the pregnancy, Resa’s mother was addicted to “doma” or betel nut. This is quite common and not considered a terrible vice even though it is known to cause cancer of the mouth. Some people chew doma only once a day, and others many times each day. Resa’s mother explained “It makes you feel warm, relaxed, and happy.” Resa’s mother chewed it up to 24 times a day, 7 days a week. The nurses scolded her in the hospital but she had it hidden in her pocket to take during delivery. This was easy to do as, this being a very modest culture, she was fully dressed in a “kira” (skirt), “wongjo” (blouse), and “dego” (jacket with pockets) during Resa’s birth. 3 – BONDING, THE “SYMBIOTIC PERIOD” A to I: We teach parents the importance of gentle handing of the newborn, of soft clothing, and detailed attention to the environment as it will be experienced by the newborn. Also we teach the importance of limiting visitors to the family of a new baby to the first two weeks, giving the newborn a chance to get to know the parents and siblings, attaching visual and sensorial information to the voices the baby has heard during pregnancy. Bhutan: In Tibetan Buddhism harsh speaking, anger, and other expressions of negative emotions are considered mental deficiencies that one should learn to eliminate. As a result, calm, soft speech and gentle behavior are a natural part of the baby’s environment from the beginning. Bonding in the first days is protected in Bhutan by an ancient tradition. Because the walls of traditional homes are made of pounded mud there is no water source in the home, which could cause the destruction of these walls. Even toilets and bathing containers are kept outside the house. Because of this lack of water in the home, standards of cleanliness are different, and after a home birth the home is considered polluted. No one is permitted to visit until a cleansing ceremony or Buddhist “puja” is carried out.

Most families are actively involved in farming and the traditional farmhouse has three stories accessed by stairs that are more like ladders. The first floor of Resa’s family’s farmhouse is occupied by the farm animals and is a storage place for grains. The second floor contains the kitchen, bedroom, living/dining room, and a large prayer room with an altar that takes up a whole wall, and is very beautifully decorated with carved wooden masks, paintings, brocade cloths, carvings, statues, oil lamps, flowers and fruit offerings, and incense. The third floor is partially open to the air as it is the place herbs and peppers are dried and crops stored over the winter. Resa’s “puja” was held when she was three days old as is the tradition. Three monks were hired and the event took place in the family prayer room. For 2.5 hours, as the family went on with their farming and household duties, the monks chanted prayers, burned incense, played the Buddhist horns, large and small drums, and bells. Then they were given lunch. When the celebration was over, the rest of the family, those who do not live in the house, arrived with gifts of clothing and food. As a result Resa had three full days alone with her family, putting the faces and the smells of all of these people together with the voices she had heard during pregnancy. She was able to get to know her own family in a new way. 4 — SLEEPING A to I: There are two things we learn in the Montessori course that help support a child’s healthy habits of sleeping. The first is to respect the child’s own wisdom of when to sleep and for how long, never awakening him when he is sleeping. The second is to give a child his own place to sleep where he is safe, where he can explore the environment visually (no crib or playpen bars), and that he can get in and out of at will when he is ready to crawl to explore the room (a mattress on the floor). In the West couples generally have sex at night in their own private bed. If the baby is kept in the parents’ bed every night from the beginning of life there will come a time when the parents want to resume their sex life. Then the baby will be moved out. The infant can be confused and hurt by this seeming “rejection”. However, if he has been used to sleeping in his own bed at least some of each day or night since birth, the move will be more natural, less traumatic.

Bhutan: When she was not being carried on someone’s back, Resa was placed on a blanket or woven mat on the ground. She could go to sleep and wake up according to her own natural rhythms, in the fresh air when the family was harvesting apples or rice, or wherever the family was inside the home. There is a strong taboo against waking a sleeping person as sleeping and dreaming are considered very important states of mind. As in many places I have been in Asia, there is one main room for sleeping for the whole family. Bhutan is freezing cold in the winter months and there is no heat, so sleeping together in one bed is how a family keeps warm. Before Resa was born, the parents and 6-year-old sister slept together. Immediately after the birth Resa slept with her mother for a while and later in the family bed with her sister and parents. One very big difference in cultures where families sleep in the same bed forever is that nights are not for sex. Beds in the night are for sleeping, for keeping warm, for being safe, not for sex. In one modern home where I stayed in Bhutan there are two bedrooms, but who-sleeps-where depends on many things. One night the son was sick so the father slept with him to comfort him. If the daughter or son fell asleep in the parents’ bed they stayed there and one of the parents slept in the child’s bed. When an uncle was visiting the son slept with him because they were great friends and a visit is special. Clearly in this more modern home, the family is only gradually making the transition from one bed for the whole family to the “modern” way. 5 - FOOD A to I: Of course breastfeeding is the recommended way of feeding the baby whenever possible, and nursing when the baby is hungry, not on an imposed schedule. The Montessori Assistant to Infancy is taught the importance of the mother-baby eye contact, a quiet atmosphere, allowing the baby to completely empty one breast and detach naturally instead of interrupting, avoiding distractions such as reading, watching TV, or talking on the phone during feeding. Breastfeeding is a powerful first experience in a relationship between two people and creates a foundation for intimate relationships throughout life. At around six months, when a child can sit up naturally, and for other reasons, we introduce other foods gradually at a low table and chair, with tiny silverware, and a small glass in order to follow the child’s desire to be independent and learn new skills. We do not recommend bottles unless there is an emergency. This is new information for a lot of parents in our culture, but not the case in Bhutan. Bhutan: Resa’s mother had breast fed Resa in a manner that was consistent with Montessori A to I teachings, but since TVs and cell phones are now making their way into Bhutan, this was an area where I could validate their traditional practices, and protect mothers from falling into modern habits that do not support healthy feeding. During early nursing months Resa’s mother ate more chicken, lots of milk, milk tea, beef, and eggs. One monk told me that, when he was a child, he and his siblings were very happy when a new baby was born into their family because that meant the mother would then eat more eggs. Eggs are an expensive delicacy in Bhutan and when a mother needs more eggs she shares them with the rest of the family. Ema datshi (pronounced ay´ma dot´si) is a favorite Bhutanese food, the national dish. It is a recipe of onion, garlic, oil, tomato, homemade cheese, and jalapeno-type peppers! A variety (with various vegetables but always hot peppers and cheese) is served daily with red rice, sometimes for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. During the early nursing months the main thing Resa’s mother missed was this dish as it gave Resa diarrhea. Traditionally, when the baby is around two months, a mother prepares a cooked meal composed of rice flour, water, butter, and salt—boiled till thick, puts it in her own mouth with her hand, and then from her mouth to the baby’s. Now that spoons have been introduced to Bhutan, Resa received this meal from a tiny spoon instead of her mother’s mouth. Unfortunately at this time Resa was also offered a canned cereal from India in another new invention—the plastic baby bottle. I was asked if it was true what the advertising claimed, that canned “Cerelac” was better for the child than mother’s milk and a cereal that has stood the test of hundred of years. You can imagine my answer.

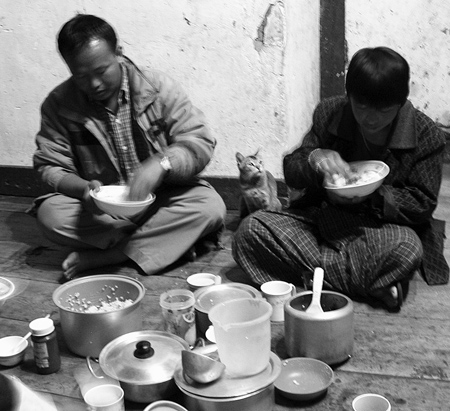

As far as Resa’s learning to feed herself, this was easy and natural for two main reasons. First, because chairs are newly introduced to Bhutan, as in many Asian countries, and meals are taken on the floor. Second, because food is scooped up and placed in the mouth with the right hand instead of with silverware. This means that it was very easy for Resa to imitate those around her, to sit up as soon as she was able, and to feed herself as soon as she was interested and capable of doing so. By one year of age Resa was eating everything the family ate with the exception of the hot chilies. And she was able to feed herself. At 18 months she still nursed from her mother once or twice a day, in the morning before her mother left for work, and in the evening. 6 – MOVEMENT, LARGE AND SMALL MUSCLES A to I: In the first year each child has his own calendar of progress in the development of such small muscles as in the hand and wrist, in the use of legs and arms for crawling, pulling up, standing, walking, and in achieving balance to carry objects while walking. We learn to observe their attempts and to arrange the environment in such a way that the child can practice any of these evolving abilities at any time, without depending on an adult. We withhold the temptation of giving the child our hands and pulling him up to practice walking, or to use walkers and other movement aids that give the message that the child’s efforts are not good enough. We provide a variety of rattles and other toys that allow the child to practice various muscle groups of the hand. But we leave the choice of what to handle, and when, entirely to the child, trusting his inner guide toward optimum development. |

Bhutan: Resa was not rushed at all in these developmental milestones. Eating, talking, doing handwork, all are done on the floor or on a low stool in a Bhutanese home so it was easy for her to observe and imitate others. She was free to explore and wander the house. When she was first learning to crawl, the doors to the landing were kept closed because access to the upper or lower floors is by ladder and not safe. The doorjambs of doors between rooms are 6-8 inches high for a very interesting reason: It is believed that the spirits of dead ancestors, called “days” are still with us. Sometimes these ghosts are frightening or angry. It is believed that, even though they still have their human shapes, they do not walk like humans but instead shuffle, sliding their feet forward instead of lifting them. High doorjambs prevent them from entering the rooms of the house. Whatever the reason, these door jambs help keep a child who is just learning to creep and crawl safe. A Montessori teacher from India explained to me that the same high doorjambs exist in her country, and when a child first learns to climb over the doorjamb it is considered an important milestone of development and marked with a special celebration. Special toys for children are not part of this culture, but children are free to handle objects in the adult’s world. Cooking utensils, pots and pans and dishes, woven baskets of a variety of toasted grains served with milk tea, craft materials, rice stalks being gathered in the fields, balls of colored thread awaiting the loom for weaving the beautiful Bhutanese fabrics, a variety of interesting objects are there to be explored and Resa was able to follow her interests, and improve dexterity and eye-hand control by handling and touching anything that was considered safe. FROM AGE ONE TO THREE YEARS1 - LANGUAGE A to I: Attention to the use of respectful and precise language when in the presence of a child continues throughout the years from birth to three. We help parents understand the negative effects of TV and too much radio. We share the importance of providing a rich vocabulary or formal language (e.g., poetry, songs), and the language of the child’s environment. Most of all we stress the importance of listening to the child with one’s full attention, talking to the child in a normal voice instead of baby talk, and exposing him to a rich exchange of language by others in the environment.

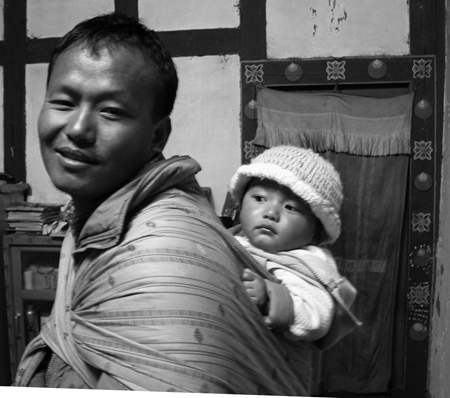

Bhutan: From birth on Resa was with the family, often carried on the back of family members and friends in a long specially woven, cloth or “kamnay.” Or she was sleeping in the same bed as her mother or the rest of the family, or with them in the home, the field, or while visiting others. Thus the exposure to language was rich. I observed over and over that babies and young children are spoken to with respect and without the “baby voice” so common in our cultures. Because Buddhists believe that we come back again and again in different bodies, they respect the full-grown spirit who has gained wisdom throughout several lifetimes and is not beginning life as the “clean slate” of John Locke. The attitude toward proper names is unique in Tibetan Buddhist culture: very little importance is given to a person’s name. People in the past in Bhutan only had one name and having two is a recent development. The name of my hostess, who received her Montessori diploma in Thailand where we met, is “Dendy”, but she and her husband have given their children two names. If someone has two names, such as Sonam Dechen, and one asks which one to use, the answer is often “It doesn't matter.” A baby is called “Oh” (which is Dzongkha, the language of Bhutan, for “baby”) until a name is chosen at the temple. At the end of 3 months, Resa was taken to the local temple to be named. A bamboo basket containing many rolled up pieces of paper had been placed on the altar. Each paper had one name written on it. Any name can be used for either a boy or a girl so this was not a consideration. Her mother selected a piece of paper, unrolled it and saw the name “Resa”. There was, as is the tradition, no discussion; that was her name. To be modern her parents gave her a second name so she is officially Resa Lhadon, but Lhadon is not a family surname; Resa’s mother is called Sonam Zangmo, and her father Karma Drukpa. Music is a very important part of Bhutanese culture and there are many folk songs just as there are many traditional stories. At bedtime Resa’s parents or grandparents sang to her. By age one and a half Resa knew many songs and the names of many of the objects in the home. When I wanted to take her picture and her grandmother told her to look at the camera, Resa, who was busy cleaning up spilled water said very clearly, “I don't want to.” Television and radio have entered Resa’s home and seem incongruous in this ancient farmhouse. The radio broadcasts Bhutanese songs all day, and the Bhutan national TV station airs a program that plays Bhutanese songs for one hour a day and “Mr. Bean”, a British animated series. From these programs Resa has learned many songs and to dance like Mr. Bean. It is common for a child at age one to watch TV for two to three hours a day. So, at their request, the family and I had an interesting discussion on the subject, and how it has lead to in increase in materialism, violence, and overeating in the West. 2 – MOVEMENT AND INDEPENDENCE A to I: At around one year the child learns to walk. Now he is interested in the skill of running, of walking carefully, of walking for long distances pulling or carrying heavy loads, in doing real work in and outside of the home. He also has an instinct to refine the movements of his hands in real work, cooperating with the rest of the family in the work of the home. Some toys, such as blocks, balls, bead stringing and puzzles, contribute to this progress, but better are real child-size tools, where he has the choice to do complicated, challenging work that is real. Bhutan: As I have said, very few children in Bhutan have toys. I have seen a school playground with more than one hundred elementary children at recess. There were no climbing structures or swings and no balls or toys. It was amazing to see the circle games and other constantly changing games the children invented, and their creativity with stones used as jacks, a ball-shaped rock for rolling, a hacky-sack made out of rubber bands.

Resa was constantly on the move, or sitting thoughtfully and silently engrossed in listening to an adult conversation or watching the adults’ actions and interactions. One afternoon as I was visiting the family, Resa began to cry and her sister went into the kitchen and returned with a glass of milk for her. The sister spilled some on the floor, returned to the kitchen and came back with to cloth to wipe it up. As the sister entered the room Resa stopped crying, reached for the cloth, and proceeded to clean up the spill. Seeing her interest the sister took a container of water and made several more puddles for her little sister to clean up, which she happily did. This continued until Resa was satisfied. This was a fortunate occurrence as I was then able to point out that doing real work is often more important to a child’s happiness than food, and that Resa was probably not crying for hunger but for lack of something to do. The family agreed heartily since they recognized this in themselves. When we were leaving, my hostess Dendy went into the prayer room to light incense; she bowed her head and put her hands together in prayer, and then began to place a money offering on the altar. Resa was standing next to her and reached for the 5-Ngultrum note. Dendy automatically handed it to her so that Resa could be the one to place it on the altar.

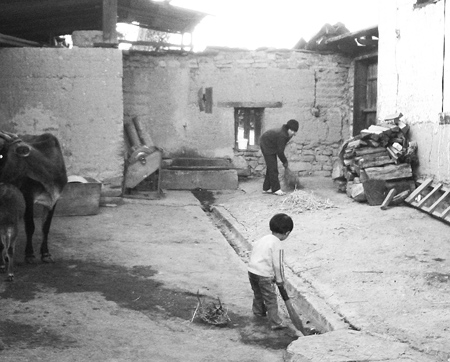

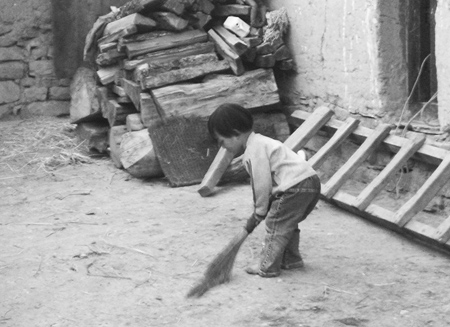

As we climbed down the ladder to the ground floor and crossed to the door to the wall that surrounded the home, we saw that Resa had followed her sister out and was joining her in sweeping up loose hay and horse droppings.

In none of these instances did adult facial expressions change in such a way as to show that this inclusion of Resa in any activity in which she chose to participate was anything but normal behavior. There were no comments such as “Oh, isn’t that cute. Resa is doing this all by herself.” It was clear that Resa was able to participate at will in the life of the family and in so doing, refine her movement and reach an ever higher level of independence and responsibility.

3 – DRESSING AND TOILET LEARNING A to I: In our culture, parents often need a lot of help to understand the importance of a child’s learning to dress and undress in aiding self-respect, independence, and physical development. And the hundreds of books on the subject of toileting are often more confusing than helpful. We use the term “toilet learning” because it is better to think of the child “learning” rather than “being trained.” Both at home and in the Montessori Infant Community, the emphasis is on preparing the environment that supports a child’s ability to teach himself to take care of these natural functions. I recommend the book “Diaper-Free Before 3” which follows our system very closely. Bhutan: As in most developmental stages of children in Bhutan, learning to dress oneself and use the toilet are just skills that a child is expected to learn when they are ready. They are not rewarded or punished or manipulated into learning them according to an adult schedule. I don’t think there are special discussions about them or that they present particular problems. As far as dressing and undressing, Resa wants to do everything her 8-year-old sister does. She imitates her dances, wants a school bag like she has, tries on her clothing, and so on. She wears a skirt and shirt in hot weather and long pants in cold weather. Both are easy to remove and put on. People remove their shoes when entering a building of any kind in Bhutan traditionally, so shoes are also easy to remove and put on.

It is common to see children, and sometimes adults, urinating or defecating in the fields and along the road. When one realizes that toilets have been, until recently, a hole in the ground, it is easy to see why the attitude is so casual. I have seen many adults help a child to maintain balance while squatting along the road, gradually the child learning to do this on their own. Resa was free to “go” anywhere, either inside the house or outside, and someone cleaned up after her. Resa noticed that, between the age of 1 to 1 ½, if Resa wet or soiled herself outside, she would often come quietly inside by herself, remove her pants and put on clean ones. If she wanted help she asked for it, but her mother said that she could tell that Resa was beginning to want privacy and to care for herself in dressing and toileting matters, and this was respected. 4 – GRACE AND COURTESY A to I: It is clear in the section above, that movement is clearly tied in with the Montessori Practical Life areas of Care of the Self and Care of the Environment. But the Montessori area of Grace and Courtesy deserves its own section. In the Montessori A to I class the teacher is well aware that adults are the most important elements of the child’s environment. Children study us constantly in order to learn how to be. As a result we take care with our movements, how we speak, how we use our hands, eat our food, and the words we use and our tone of voice—our all important roles as Grace and Courtesy models. Bhutan: Bhutan is the only country I have visited where there is a whole social science dedicated to the practice of grace and courtesy. The father-in-law of my hostess was a “Driglam Namsha” (grace and courtesy) teacher for students in the final year of what we call high school. This is the traditional social etiquette education intended to inculcate the habits of graciousness and a kind-natured attitude. These lessons have to do with walking, dressing, speaking, and greeting others -- many of the lessons we in Montessori call Grace and Courtesy. Because of this value of respect and good manners toward others in the culture, parents model this behavior for their children from birth on. They quite naturally use a modulated voice and gentle movements. One day when a neighbor saw me leaving the house, she reached down to the very young child in front of her, and showed her how to put her hands together and bow her head to greet me with respect. Other than this subtle guidance of a grandmother to a very young child, I did not see anyone reminding children to “say please”, “say thank you,” or all of the other reminders that we use that do not work. Instead adults are constant models that the children desired to imitate. Walking is the common way to get from place to place in Bhutan and it is not uncommon for children to walk more than an hour to and from school, or for people to walk for miles with loads of hay on their backs, or carry food from the outdoor market back to the home. One often sees a person, who is not carrying something, offer to share the load of someone else. When one is lucky enough to have a car it is common to pick up people who are walking until there is no more room in the car. Every time we arrived home in the car with food or other packages, the children ran out of the house and asked to help carry things into the house. Even when I was going upstairs to my room, if one of the children were there I was not permitted to carry anything. An afternoon snack consists of salty milk tea mixed with a toasted and ground grain called “tsampa.” This meal has been eaten for hundreds of years all over the Himalayan region. When we had this at Resa’s house, not only did she mix her own tea and tsampa, but then she mixed mine. Such thoughtfulness and kindness is common in children as much as in adults. SUMMARYThere is often a tendency to romanticize or idealize cultures that have not been “corrupted” by the influence of the west. I hope I have not done this here. There are good and bad elements of all cultures. Bhutan is beautiful and spiritual, but there are rats and lice and leeches, toilets that are just holes in the ground, and systems of modern education and medical care that are available only to a few. It is an honor to be in a position to work in Bhutan. I have been there for only two short visits and so I am just beginning to learn about Bhutan. My first visit to Asia was in 1964, and I earned a degree in Comparative Religions in 1969, and since then I have been very interested in this part of the world. In 2002 I met the Dalai Lama and studied under a teacher who had come with him from Tibet to India in 1959. I think it is because of this experience, and the fact that I have a Buddhist Dharma name “Sonam Dechen” by which I am always introduced in Bhutan, that I have been welcomed into the private lives of Bhutanese families. My role has been to validate what contributes to a healthy upbringing and education in this culture, and to share with these parents and teachers what we in the West have learned is good and bad about modern culture. Montessori has been shown to work with all children throughout history and all over the world, but it must be adapted, especially in the practical life, language, and cultural areas to the time and place of the children of each country. When their own culture is respected, the door is opened to an interest in and a respect for all other cultures, and a step toward world peace. |

More 0-3 Information For more 0-3 informatioin see the chapter "Montessori at Home" in the book Aid to Life, Montessori Beyond the Classroom: Aid For interesting links and a source of some 0-3 products, return to www.michaelolaf.net Author's bio More about Bhutan After hearing about Bhutan, many people ask me about visiting. One of the ways that the country has been able to keep their farming economy stable and healthy, and to protect the environment, is to restrict tourism. There are still very few roads in Bhutan and relatively few cars. There are no traffic lights. Religious sites are used daily by the Bhutanese. Therefore it is necessary to visit the country as part of a tour so that the sites will not be overcrowded, and the traffic will not be too difficult to handle, and the culture will not be destroyed. Please contact your local travel agency to be directed to one of the many tours if you are interested in visiting Bhutan. There are more pictures, and details of life in Bhutan at this site - 2006 trip: http://www.michaelolaf.net/bhutan.html Susan's email's home from the third trip to Bhutan, Spring 2010: http://susanart.net/bhuthaifeb2010.html |

|

|

|