The natural urge to sing, dance, to make and listen to music wells up from the depths of each person, from birth to death. It can be stamped out at an early age or it can be fostered to enrich all of life. In this article you will find ways that music is important to us at every stage of life. What is music? What words can accurately describe it? We might as easily try to capture all the most poignant sights, sounds, and smells of childhood holiday celebrations into a single black and white collection of letters on a piece of paper! We may not know how to fully describe music but we do know that we don’t want our children to miss out on it.

I have heard fascinating presentations by Adele Diamond, neuroscientist, both at the Annual General Meeting (AGM) in Amsterdam and at the AMI Educateurs sans Frontières (EsF) Assembly in Thailand in 2015. Dr. Diamond contributes a lot to the Montessori movement of nurturing children because she studies how executive functions—including the abilities to think outside the box, mentally relate ideas and facts, control impulses, focus and concentrate—are affected by biological and environmental factors. Recently she has turned her attention to the possible roles of music and dance in improving not only executive functions, but also academic outcomes, and mental health. In dozens of recent talks she points out that there is a reason dance, play, storytelling, art, and music have been part of human life for tens of thousands of years and are found ubiquitously in every culture; that perhaps we have discarded the wisdom of past generations too readily.

We need to look back…There was wisdom in previous generations that we’re ignoring…We think we’re going to be ‘modern,’ and that we can do better than our parents and grandparents. There are things that have been part of the human condition for thousands of years—that have been part of the human condition for good reason; otherwise they would have been weeded out.—Adele Diamond, PhD

Music is made of vibrations felt by the ears and by the whole body. The lower notes, the longest and slowest vibrations, are felt by the human body as touch. Beethoven in his last and very productive years as a composer was completely deaf. So he had the legs removed from several grand pianos and composed by sitting on the floor, feeling the vibrations from the piano strings and the piano wood enter his body through the floor. Today technology has been developed that can do the same thing for deaf musicians. The effects of different pitches, intervals, and timbres evoke different responses in us. Part of this phenomenon is cultural, but it is also psychological and physical. Experiments with plants show us that the music of Mozart and the Indian Ragas support growth and health while loud rock music can cause plants to die.

Wisdom from the past says that there exists a music of the spheres, as electrons spinning around the nucleus of the cell and as the planets spinning around the sun. Laurens van der Post discovered some of this wisdom as he got to know the Bushmen or San of the Kalahari:

As long as the Bushman heard this sound of the sun and stars and could include it in the reckoning of his spirit, all was well in his world. The howl . . . reached me and seemed to change into a minor scale the major key of the music of the stars which resounded over the vast full-leafed garden beyond.

—Laurens van der Post, Witness to a Last Will of Man

MUSIC AND THE STAGES OF LIFE

PRENATAL

From the first cell, the human infant begins life in touch with the rhythms of the mother’s body. As he grows up, his experience becomes more focused, more refined, sensitive, and educated. Montessori teachers are devoted to keeping the development of humans as close to the divine plans as possible in all areas from birth on, and to do this we must do all we can to keep the child in touch with music. He is the human link with the universe, the past, the future, all of nature, and with other humans.

It is a combination of many different sound vibrations that the child hears in the womb. The rhythm, the pitch, all of the subtleties of sound are taken in by the developing human, in ways we do not yet understand. The child is constantly exposed to, and responding to, the internal sounds of the mother’s body and the external sounds of the larger environment. Many cultures of the past understood this enough to have the best musicians play for the unborn child and for the mother to sing a special song to each yet unborn child. Scientists today can trace the specific muscles which are stimulated by specific sounds. Language tapes played before birth may stimulate the “music” of a second language and improve the child’s ability to learn both before and after birth. Many mothers know that children keep time to external music by kicks and other movements and that a piece of music sung or played often enough before birth will be recognized by the child after birth and can have a calming effect on him.

Just as the child moved in response to sound in the womb, he does this after birth. Notice a joyful baby kicking his feet wildly because someone is talking to him. It may be that this movement begins to lessen in response to spoken language, but it definitely continues in response to the elements of music.

BIRTH TO AGE THREE YEARS

The newborn child responds to sounds and other experiences, such as a loud crash or a familiar face with his whole body – clenched fist, thrown-back head, great smile accompanied by wildly, joyfully kicking legs, or sometimes the motionless stillness of focused attention and study. It may be that the lack of music in our culture at this stage accounts for the fact that this movement expression tapers off as our children grow, because it certainly continues in children from cultures where music and dance are a daily part of life. Percussion instruments provide more variety in the natural inclination to move and clap rhythms.

Dr. Montessori spoke of this period of life as the time of the “unconscious absorbent mind.” During these years the child develops in response to what he finds in his environment. Today some scientists believe that if the cells that are designed to be stimulated by sound are not so stimulated by eight months of age, they will begin to die off. We already know that certain sounds are detrimental to health and others are supportive. So we have a great responsibility to examine carefully the sounds in the child’s environment.

In the first few months of life the child will begin to make music with his voice. I have often had the joyful experience of beginning a singing dialogue with a child at this age. When the child makes a cooing sound, we can repeat the pitch, the time, the length of the sound. Very rapidly, the child will catch on and begin to make a variety of more and more sounds intentionally. If we carefully imitate these attempts, longer and longer joyful duets of music will result. This is a very important experience in the development of the child’s self-image, his attitude toward communication, a preparation for singing and talking.

In the early days and months a child is attracted to faces and carefully watches the faces of the person who’s talking and singing. When we change or bathe the child it can be disturbing if we distract the child with toys, or to rush the task, to get it over with. It is better to relax, smile, and explain what we are doing while looking at the child’s face. Slowing down and involving the child gives a feeling of respect, of belonging, of communicating, and it provides a wealth of vocabulary about the child’s world. If we sometimes sing this communication, we give a wider range of pitch and the vocabulary of music. This is interesting to the child and he will focus and listen. These moments of dressing, changing, and bathing then provide important quality time of communication between adult and child.

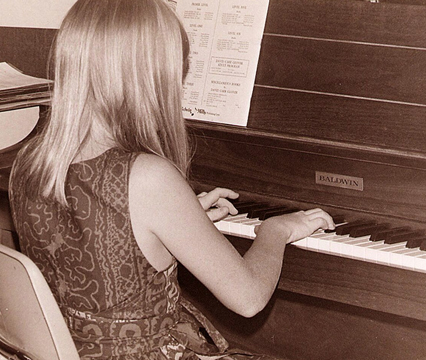

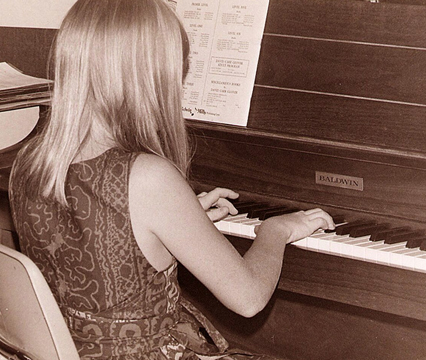

The year I was taking the AMI Assistants to Infancy course in Denver, Colorado there was a piano in one of the course rooms that I played when we were on break. I remember Dr. Montanaro, my trainer along with Judi Orion, coming into the room with a slightly distressed look on her face. At first I thought maybe the music was disturbing to others but then she said, “We must find a way to let the children in the Infant Community in this building watch and listen to you.” This brought home a very important point she had made during one of the neuropsychology lectures -- that from an early age children should be shown music being created by the hand and the movement of the human body.

Since then, having been brought up in a family where everyone played an instrument, I have been very surprised to discover that many children have never seen this. When music always comes out of a car radio, a CD player, how can children be inspired to make music? Wherever I go now in international work I look for ways to share this experience, either by percussion sounds or a piano when I can find one. Even the youngest child, as in the picture above, delights in being shown how to touch, to pull on a guitar string gently so that the sound is the same as when the adult does it. The development of the hand and movement of all kinds is something that children at this age are very interested in.

As adults we have the ability to close off unpleasant sounds, but the child does not—he hears everything. One day I was in the bedroom reading to my young grandchild. Suddenly he looked at me and said, “Bird!” I put the book down and listened and could hear some crows far up in a tree outside our window. I would never have heard them if my grandson had not shared his experience with me. In the home and the Montessori community, we should pay special attention not only to what can be seen, touched, tasted, and smelled, but also what the children are going to hear. If the child is in an environment where the sounds from a TV, a passing car, a wind-up toy, music from the radio, the running of a dishwasher, etc. can be heard, this is the “music” the child will become accustomed to and will want to recreate in his life. If the child grows up with this cacophony, he will continuously try to recreate it in his life, no matter how detrimental it may be to his body, mind, and spirit. If he is in an environment of peace and quiet, soft beautiful voices and lovely music, he will recreate this in later life and be nurtured physically and emotionally.

In the Montessori Infant Community the children have a strong sense of order, not only of place or environment but also of schedule. So the morning can often end, after a snack or lunch, with singing. But the teacher is also very likely to sit down at any time of the day to give a language lesson to one child or to sing a song with one or two children. Because children are not required to come to these lessons and because they love the language and music, many, if not all of the children, will participate, being free to go back to other work at any time. Concentration on independent work is always considered more valuable than group experiences.

The period of these first three years is the most intense in all of life for storing up sensorial experiences. We do not talk baby talk to these children because we know that this is the time when they are absorbing the music, grammar, and vocabulary of the language he is exposed to daily. For the same reason, we do not limit their musical experience to baby music. As long as we carefully observe the children and their response to the music we offer, there is no limit to the music we can provide.

AGE THREE TO SIX YEARS

During these years the child learns to sort, classify, and arrange the sensorial experiences that began in the first three years, to organize the brain and to make the information available for creative expression. If supported by the environment, children at this age can easily and effortlessly learn to write and read music and to play instruments. It is thought that rhythm instruments were the first used by early man, and this is a good place to begin with children. In their hunger for spoken language it is the easiest time to learn the names of pieces of music and composers, not for this information on its own, but so that they can ask for and talk about the music of their choice. As we give children the elements of culture it is quite natural that we give them the music of all cultures.

During my AMI 2.5-6 training at MMI (then MMTO) in London, I did part of my student teaching in a school in St. John’s Woods. One day I saw a very young child walk up to the teacher, look up at her, and as the teacher bent over to be closer, whisper something in the teacher’s ear. Of course I couldn't’t hear the words but from what followed I think she said, “Can you give me a dancing lesson.” I often tell this story today when I am consulting with a school where help is needed to implement the 3-hour work period that is required in an AMI school. I hear, “But when will we sing? When will we dance? When will we read books or tell stories or share poetry or nursery rhymes or finger plays which we are supposed to do every day?”

My reply is to: “follow the child and do them at any time during the day with one child, or a few children, but never on a schedule.”

Let us return to the dancing lesson. Together the teacher and the young child cleared a small space in the classroom by moving a table and a few chairs. Then they removed their inside slippers and placed them under one of the chairs. Then together they went to the tape player (this was before CDs were invented) and selected a tape, put it in the player and turned it on. The music played quietly and the two of them danced, in the style of the greatest of modern interpretive dancers, to the rhythm and energy of the music. When it was clear that the child was finished they put their inside shoes back on, put the tape back in the box of tapes, and the chairs and table back where they were. Everyone in the classroom around them had continued with their work undisturbed so it was clear that this was a common event, a 1:1 lesson.

There are many old and traditional songs that have appealed to children throughout the ages. But the first six years of life, the absorbent mind years, is the time to expose children to the music of their own culture, of other cultures, and the classical music of the West for it was influenced by the music of much non-Western music, for example Ottoman martial music, which was in vogue in Vienna during the 18th century. Also Satie, Debussy, Ravel, and other French composers were influenced by Javanese gamelan music, and Gustav Holst's opera "Saavitri" was inspired by the Indian classic Rig Veda.

Ali Akbar Kahn, the famous musician from India, prefers Indian music to all others. But his second choice is the music of Bach and Beethoven. The last five hundred years of the development of music in Europe have been the most varied and profound of any on earth. Anywhere in the world one can hear music from this tradition. It is indeed an international language.

As part of my A to I (0-3) training our family went to Rome. We stayed at a convent where preschool children attended classes during the day. Our son asked permission to practice on the convent piano. As he began to play western classical music the children from the preschool came from their classroom and gathered around the piano, humming along because they were familiar with the classical music he was playing. Then, as he began to play the music from modern American composers, their attention wavered and started to wander back to their classroom; they couldn’t relate to this music. They were very pleased when, a few moments later, he returned to classical music. We had a similar experience years later with visitors from Sweden. The children had very few words in English and communication and play was stilted until the parents realized that all three children were Suzuki students. Just the humming of a few of the Suzuki pieces caused the curtain of strangeness and isolation to fall away and a feeling of belonging to the same community took its place.

One year I was consulting with a school in the Bahamas and helping to set up a music appreciation set of music CDs representing the continents of Asia, Africa, North and South America, Australia, and Europe. The owner of the school already had a fine international music CD collection so it was easy to select one for each continent. We labeled the front of the CD case with an image that matched the colors and shapes from the continent puzzle map. Children were free to select and play any of the CDs at any time during the morning 3-hour work period, the volume control having been set on low permanently with a metal staple so the music was not too loud. None of the children had been exposed to this music but it was remarkable to see that when they played, for example, the Salsa music from Colombia or the belly dancing music from Egypt, they made exactly the same kind of whole body movements that salsa and belly dancers from those countries would make. I had studied both of these kinds of dance and so noticed it particularly but I imagined that the same thing would hold true for the music of the other continents, the piano music of Chopin, the didgeridoo of the Australian aborigines. It made me ponder just what was the relationship between cultural music and the synchronized body movements, and where did it all begin?

There are other ways to include music as individual activities in the Montessori 2.5-6 class. Here are some examples.

Listening to music: Dr. Montanaro of the Montessori Assistants to Infancy training, in her child neuropsychiatry lectures, explains that earphones can have very negative effects, both psychologically and physiologically. So listening to music on a low volume CD player should be a chosen individual activity during the three-hour morning work period. Even in the Montessori infant community there is sometimes found a little corner, perhaps with a tiny easy chair and a large plant providing privacy (and leaves to dust and wash) for a child to choose and listen to music.

Playing Musical Rhythm: To become aware of rhythm, have a small group of children, each with a percussion instrument. Teach them to play the rhythm of their names, imitating the number of syllables and the rising and falling pitches. Think about how these will sound, repeating each name 5 times: A.lex.an’der, Sam, Su’san, Ur’sula, and so on.

Learning the names of musical instruments: Even in the Montessori Infant Communities one might find musical instrument models and matching cards in the little corner where one can listen to music CD’s. The picture above was taken in the 0-3 course environment in Hangzhou, China that was set up by Maria Teresa Vidales and her daughter Teanny Hertado. The same thing can be used in the 3-6 class. At this age the pictures and models do not have to match in size and color, and it is also possible to match CDs of solo instruments to the pictures of the instruments, just as we match the pictures of composers to CDs of their music.

Bring in composer tapes with the story and music of one composer. There are excellent story tapes such as Romeo and Juliet and Beethoven Lives Upstairs for individual listening.

Play music from different cultures linking them to objects, flags, and pictures from continent folders or continent boxes.

Songs: So that a child can ask for a particular song (or finger play, or poem, or nursery rhyme) at any time during the 3-hour work period, I prepared a set of cards with one song and an identifying picture. A non-reading child can go to the box of cards, look at the picture, select the one he was looking for, and bring it to the teacher or in some cases an older child to sing or read it.

Visiting musicians: Often times a parent or a family friend will be delighted to bring an instrument in and play just a few moments for the children. Be sure and explain the 3-hour work period and that children will come to their little lesson only if they choose, so that the guest’s feelings won’t be hurt if he or she ends up playing for only a few children in the class. Everyone will hear and benefit.

Concerts: In my school we had “concert practice”. Even for the simplest song played on the bells or when I would play the piano or a visitor would play, someone would make up a program, line up a few chairs, and practice concert manners, listening instead of talking, keeping hands in lap, and clapping when the performing musician finished and bowed to the audience.

If we try to think back to the dim and distant past what is it that helps us reconstruct those times, and to picture the lives of those who lived in them? It is their art. It is thanks to the hand, the companion of the mind, that civilization has arisen." — Maria Montessori

FORMAL MUSIC INSTRUCTION

What about formal music education for children? For many it is not enough to learn to sing a few songs or to read and play someone else’s music. Nor is it satisfying to the spirit to learn to recognize the music of musical periods and composers merely to label them and quickly move to the next. We must prepare an environment that protects and nourishes the music the child carries within him from conception.

There is a great satisfaction in learning to sing the words of a song, to write and read music, but perhaps the greatest elements of music are physical and emotional. The joy of feeling and expressing music with the whole body and the voice, of creating original music alone or as a group, and moving through space to these sounds has always been an essential element of human life.

There are several child-friendly ways to introduce children to formal music reading and writing. The Montessori bells are standard sensorial materials in the Montessori primary class, and children easily learn to match and then to gradate them. With enough practice a child can hear a bell tone played and know the name without knowing where in the scale it is. This is a natural skill called perfect pitch that many of us thought was either inborn or was not. Actually, it can be learned at this age and sometimes children go on to learn to read music.

In our family we have enjoyed learning music with the Suzuki method. Suzuki and Montessori are similar in that their names are used to describe all kinds of schools and classes that sometimes have nothing to do with either Suzuki or Montessori. It is important to learn to recognize an authentic Suzuki teacher. There are other similarities. For example Suzuki is called “talent education” because rather than thinking that a person either is born with musical talent or is not, the belief is that any child can be a good musician with the correct instruction. It is also known as the “mother tongue” method because just as with listening, children are not expected to be able to replicate a beautiful sound on an instrument if they have not had many, many hours of listening to the very best musicians performing the simplest Suzuki repertoire beautifully, just as we would not expect a child to explode into perfect spoken language without having heard his mother tongue from before he was born.

Another commonality, which as a Montessori teacher I could really appreciate, was the analysis of the steps of learning something, awareness of what skills must precede and what skills will follow a particular step in learning a piece of music.

One summer when I was passing through Denver, a good friend brought her 4-year-old daughter to the airport during my layover to show me what she was learning in her newly begun Suzuki violin lessons. Anne placed her violin case on a seat, carefully and deliberately opened the clasp and lifted the lid, picked up the satin violin cover and laid it over the cover of the violin case. Then she picked up the bow, tightened it and put it back in the case. Then she picked up the violin and carefully put it on her left shoulder holding it in place with her chin and her left hand and picked up the bow again with her right. Standing tall and proud she produced the first six notes of the first song in the Suzuki Violin book one. Next she tucked the violin under her right arm and slowly smiled and made a little bow in my direction. Just as carefully she put everything away and closed the case. I thanked her for her “concert.” And she was pleased. Doesn't’t this remind us of the care with which any of our young children would carry out the grace and courtesy and the early movement development work in our classes?

In 1995, as I was visiting the Suzuki Talent Education Institute in Matsumoto, Japan, I was fortunate to attend an opera lecture by the Director of the Institute. Professor Takahashi, a flutist, explained to me the purpose of his training for adults who are going out into the world to become Suzuki teachers for children. He believes that music must be first listened to, then expressed through movement of the whole body, then sung, and finally played on the instrument. During the lecture, the teacher trainees listened to a famous opera aria. Then Mr. Takahashi demonstrated the feel of the music by body movements and the singing voice. He sang neither in Japanese nor Italian, but a kind of joyful intense humming, rather like a jazz musician. The difference between the flute and violin playing of his students before and after this body-voiced expression was remarkable. Instead of individual notes his students could actually feel and express the intention of the composer and the emotion of the musician.

This is what we must pass on to our children. This is the ability with which they are born – the ability to express emotion naturally in music with the body and the voice.

AGE SIX TO TWELVE YEARS

This is the time of stable growth and interest in the morals and reasons of everything. The time when children are interested in forming groups, working in groups. This is the best time to be in a music group. It was during this time that our son formed his first rock band of two guitars, a drum set, and keyboard. The boys were so sure that they would be as famous as the Beatles someday that they labeled and filed each and every one of their rehearsals. They learned a lot of music but they also learned a lot about being patient with each other, and all of the other abilities necessary to work successfully together. In their search for an audience they performed at a homeless shelter and homes for the elderly and they learned a lot about society there as well. They were also able to give to others by making tapes of their music -- important and much appreciated gifts for their families.

Age 6-12 is a time of steady growth, not like the years 0-6 and 12-15, and so it is a steady time for learning to read, write, and play music. The ego is strong and the hard work necessary to make progress in any endeavor is pleasurable. Being in a musical group or an orchestra satisfies the need at this age to be part of a group and to adapt one’s own needs to the collective purpose of the group.

As teachers of this age we can offer a multitude of inspiring and soothing music for these searching young people. For a child who does not play an instrument I have kept a guitar, recorder and piano always ready with materials to help the child begin to play. Even a few chords on the guitar can sometimes unlock the emotion and creativity of the adolescent.

Moving to music becomes more refined, because the dances of the modern culture as well as ethnic dance from other cultures are interesting to children of this age. On the intellectual level music can be connected to history and to the migrations of cultures in the past. This year our family attended a performance of the Throat Singers of Tuva, a group of four men from a small community in the middle of the Siberian subcontinent. During the performance a single man performed an ancient Tuvan dance that mirrored almost exactly the costumes, drum, movements and music of the Plains Indians of North America. The singers are convinced that the people who crossed the Bering Straits so long ago were the forerunners of all the aboriginal Americans from Tuva. What an inspiration for the elementary child to study migrations and communication between cultures.

In 1977, I taught a 6-12 class for the first time. This was in St. Croix, US Virgin Islands. The head of school knew ahead of time that I required a piano for the classroom, so the mother of one young lady told me on the first day, “Pia is planning to be a vet, so you don’t have to give her piano lessons.” I replied that no one would be required to learn music, but I would offer beginning instruction on recorder, guitar, or piano to any student who was interested. When I was not busy during the class time I practiced a Chopin piece that I was supposed to play in a wedding in Washington DC at the end of the year, and Pia fell in love with it. It is 11 pages long and not easy and I could never play it without music, but working diligently, before and after school and during the lunch hour (after her fellow students complained about hearing the same piece over and over) Pia learned the whole thing beautifully, by memory, by the end of the year. She had never played a note of music before that. Almost 40 years later in 2015, Pia brought her husband and two grown boys to visit us and since neither of us had polished that piece in many years, I played a recording of this piece, Chopin’s Opus 64 #2 for her family. I am sure it inspired them to continue with their own musical studies.

AGE TWELVE TO FIFTEEN YEARS

As in the period from birth to age six, this time of life is filled with rapid growth and the need for nurturing. It is a time of both clinging to the past and rejecting it, and it is marked by a need for real, meaningful and creative work, and for peace and solitude.

Last year I visited Mongolia and was able to learn about how children are raised in the city and also out in the planes, living in a ger (the Mongolian word for yurt) that are moved several times a year to follow the herds. One of the responsibilities of a child at this age is to learn to guard a herd of sheep and protect it from wolves. From a young age a child will go with the adult to do this and the mark of “manhood” is when he can manage to be alone for long periods of time to do this. It has been shown that it is these hours and days of solitude that give rise to the greatest of the music, the poetry, and the songs of the Mongolian culture. In the West it is rare for a young person to have this kind of solitude, this time to process and create. It is in the Montessori idea of the Erdkinder for this age, the years on a farm or close to nature, that it can possible.

In our modern Western culture there is not much physical touching; we do not hold hands or kiss both cheeks upon meeting as in many cultures. Some think that this physical starvation is part of the reason that teenagers seem to need to hear the strong, steady vibrations of the music. Some people even think that it might bring back early memories of being exposed to the mother’s heartbeat while in the womb or while being fed in mother arms.

My most positive memories of the tumultuous years of adolescence are walking along the river in a hot Indiana summer under the shade of oak trees singing I’ll Never Walk Alone at dramatic full volume. And sitting in a darkened bedroom listing to Elvis Presley singing “Love me Tender, Love me True.” My adolescent spirit was reaching out in ways I did not understand, but found solace in music.

Along with the modern music that teenagers crave, the music of many Western classical composers can also resonate with people at this age. It can be calming but it can also mirror the tumultuous emotions experienced at this age of hormonal changes. The hopeful and joyful feeling of some of music of Bach and Mozart music can be healing; and musicians such as Paul Hindemith, who expressed outrage at war-torn Europe, can express the pain and agony that is also felt at this age. There are both simple and complex ways for adolescents to express their ideas and feelings through their own music, not only by the lyrics, but also by the speed, pitch, and timbre. This can give many the craved outlet for self-expression and original creativity and even an enhanced self-image that comes from being able to perform for the pleasure of others.

Many years ago I was a counselor at a juvenile detention center in California. The population was basically split between the children of poor black families from the slums and wealthy white families from the hills. Nowhere was this division more evident than in the music. The black music was full of rhythm, hope and spirit; it made one laugh and dance and was in stark contrast to the moaning, sad drug culture music of the white child who had every material advantage but no hope. The two kinds of music they chose to listen to expressed their experience of the world, and their feelings, and as they were exposed to both kinds of music they were brought together as a group and began to understand each other.

The power of music to affect us is true in literature and art as well as music. A poet from Sweden shared an experience with her daughter who had been sick and was not improving. Asked what she was reading she showed her mother a pessimistic modern novel. Her mother suggested some beautiful nature poetry and she began to heal. Which literature or music is “healing” to the mind or the body of course depends on the individual, and it is worth experimenting to find the right kind.

AGE 21-18 AND ADULTS

Montessori spoke of the four planes of development as the basis for her theory of psychology. If the needs of the child have been met in the first 12 years (the first two planes, 0-6 and 6-12) the young person at age 12 or 13 is reaching the first stage of becoming an adult. It can be a traumatic, hormonal few years, but when these young people are treated with the respect given our fellow adults, and given responsibility and meaning in their work, they will thrive. In the above picture we see young people of this age and adults all playing music together on the famous horsehead stringed instruments, and on other instruments, in the capital of Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia. They do not think of themselves as children.

The music these young people play as they are becoming adults will be meaningful to them, as one of the positive experiences of this potentially tumultuous time, throughout life. Music heard at different times of our lives can have different meanings to all of us because as children we stored some experiences as a synthesis of sensorial input -- the sounds, tastes, emotional state, and touch -- all of these elements “wired together” in the brain. You may have experienced the result of this phenomenon – a musical experience in the present that unlocks the drawer of memory from the past that comes flooding back, rich in its sensorial completion.

I remember a few years ago telephoning a friend and getting her answering machine. The piece of music that I heard at first shocked me. Then I felt warmth of joy flooding through my body and tears came to my eyes. The piece was a short section of a Mozart sonata that my mother used to play on the piano and I had not heard it since that time.

In our son’s life we witnessed something similar. When he was ten I happened to be playing some Scott Joplin music on the piano that I had never played in his presence before. At the beginning of one piece, his attention became riveted to the music. He begged me to teach it to him. Although he was not ready for this music, we found a simplified version, rewrote it to include subtleties which he insisted must remain, and he worked until he learned it. What was the reason? Finally, discussing it with his father, we realized that during the summers when he was between the ages of 1 and 4 years of age, the ice-cream truck announced its arrival on our street with this piece.

As adults, we all have the experience of returning to not only a piece of music, but also the lyrical words of a poem that evoke an emotion which we feel stuck inside us, which needs release. There is a poem by James Whitcomb Riley called Little Mandy’s Christmas Tree, which I cannot read without crying. I grew up in Indiana, the home state of Mr. Riley, and experienced many of the elements of this poem in my personal life. In the Montessori elementary class for children from the ages of six to twelve, one of the main lessons is about the power of language, through which humans can reach out over miles and centuries and touch the soul of another. The children used to ask me over and over to read this poem, to watch my response, and to have to help me with the ending. Music, because it is more universal than the language of one group of people, has even more power to touch us.

In my own experience nothing can lift my spirits like moving to the music of the sixties or hearing beautiful music played with sincerity. The most important memories of my life are linked to music – hearing my mother play Grieg’s March of the Dwarfs, as she made up a story about Norwegian trolls having a picnic in the woods, or lying in bed at night listening to my grandmother play the harp until my sister and I fell asleep. For healing the spirit, my first recourse at any time of joy or grief is to express these emotions at the piano. This ability, and none other, is the satisfying result of years of piano lessons. When my first daughter left for two years in the Peace Corps in Africa, my grief was terrible. It bubbled up inside me until finding escape through the piano. Music has power and it is there for us.

GROWING OLD AND DYING

My mother was a musician and as she entered her 80s it was becoming difficult for her to play the harp or piano. I know Montessori has helped the elderly in many ways for years, but I wanted to find out how to help my mother with music. In 2014 I saw the movie Alive Inside, which won an award at the Sundance Film Festival. It follows the work of a social worker who founded the nonprofit organization “Music & Memory.” Oliver Sacks, the renowned neurologist and author of Musicophilia: Tales of Music and the Brain, is one of the people interviewed in the movie. The following year it was very exciting to hear of a new group being formed by AMI to research the needs of the elderly. AGED, or Advisory Group for Ageing and Dementia was first presented at the Annual General Meeting or AGM in Amsterdam that year. The following summer one of the presenters, Anne Kelly, also spoke at the EsF (Educateurs sans Frontières) in Thailand where she guided me in helping my mother.

Knowing well the miraculous effects of personalized music on loved ones, Anne explained that it is the music of early childhood, the music our parents play when we are young, that is the most successful in helping the elderly. So our family researched the music of the 1920’s, purchased 50 pieces from Amazon and downloaded them to an iPod and wrote out directions for her to listen to this music on a very comfortable set of earphones. Earphones are used in this case so that an elder can listen at any time without disturbing others. This week when I was with my mother as she listened to music, even though she has trouble remembering many things, she was thrilled to be able to remember the words and titles of songs. And a friend of hers (in the above picture) asked to borrow the earphones and then she also started smiling, singing, and tapping her feet. Anne says that this is not just for happiness, but it actually makes positive changes in the brains of the elderly.

My husband has formed a small music group that visits elder care facilities. He plays the guitar and they all sing. Jim often comes home with stories of how residents who previously would not smile or speak come to life when they hear a certain song. Sometimes upon entering the room he will hear a certain resident who seems to have been waiting for them all week call out his favorite song title in a loud voice, or sit up straight, clap, and start singing the words even before the musicians begin. Just as with very small children who cannot keep from dancing when certain music is played, this music stimulates the memories, movement, and language of the elders.

One of the most valuable things I learn in working in many countries is that death is often in the consciousness of many people in positive rather than fearful ways. For example, upon entering the Asoka Buddhist community out in the countryside in Thailand, a place where people share tasks as a large family, the first thing one sees is two glass caskets containing the black mummified remains of the couple who started the community. Beautiful tropical plants and flowers surrounded the caskets and the singing of children can be heard in the distance. This is meant as a reminder of how we will all look this way in the future, and it serves to elevate the preciousness of the present. I remember driving from Thimphu to Paro, Bhutan. In the past this would have been a 2-3 hour walk, but now there is a road. The elder in the back seat continued throughout the drive to finger the beads of her mala and repeat a singsong prayer or chant – as though wanting to have these words on her lips as she breathes her last. And I will never forget being in Hong Kong and seeing caskets piled high out to the sidewalk in an open front casket store right next to a McDonald’s. People can munch on their hamburger while they ponder their burial.

When I return to the USA I am even more aware of how we hide death, and often try to keep our bodies looking younger than they are as though by some miracle we will avoid this stage of life entirely. I feel sorry. As T.S. Eliot says, We shall not cease from exploration, and the end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we started and know the place for the first time.

I have heard that in Hawaii the tradition is to gather at the bedside of a dying person to pray and sing. So I have paid attention to the favorite music of both of my parents. When my father, a physicist who loved music, was 84 he was in the top of a tree cutting branches to allow more sun to reach the solar panels he had installed on his greenhouse. He fell out of the tree and three days later he died. In those last hours he was unresponsive but we could follow his heart rate, etc., on the hospital monitors. We brought in his favorite CDs of Bessie Smith and jazz musicians. It was clear to everyone that he was responding to this music. We all stood around his bed and said goodbye as he left us listening to music that had cheered him in life.

Our son has made my husband and me several CDs containing our favorite music. We listen to it in the car and in the house so we are ready. Suo Gan, a traditional Welsh lullaby, is one that always relaxes me and brings a smile. And those of us who took the A to I (birth to three) AMI training will always remember how The Adagio in G Minor, by Antonio Albinoni, which we use to train mothers to relax between contractions while giving birth, always makes us sink into a relaxed and peaceful meditative state. It will no doubt be a choice for end-of-life music for most of us. Maybe, as part of a living-will it is a good idea for all of us to make a list of our most uplifting music to escort us to the next step in a most humane way.

Silvana Montanaro, MD, told us during the A to I training that a crisis, even though it is usually painful in some ways, always opens one to the possibility of more freedom and should be celebrated. This is true for birth, for weaning, for learning to walk, and maybe even for death. As we follow our Montessori way of discovering and supporting the best in human instincts and wisdom, perhaps we can keep this in mind as our elders leave us.

Humans are not just a body and a brain. There is always a part of us searching for balance and wholeness. I believe that music has a lot to offer.

To quote Dr. Montanaro:

In Western education we tend not to appreciate the whole potential of the brain because many of the things the right hemisphere (intuitive) is able to do are not highly valued in our civilization. So from a very young age, children learn not to express themselves completely with that hemisphere because they haven’t been urged to give much importance to body movement in dancing, singing, and drawing, all of the arts. In Eastern civilizations, however, greater importance tends to be given to the intuitive part of the brain; the logical hemisphere is considered irrelevant in solving the real problems of our existence.

A new form of educational system will not appear until we give serious consideration to the fact that we have a ‘double mind’. Children at any age must be offered a balanced experience of verbal and intuitive thinking to help develop the great potential of the human mind. The results will not only include better functioning of the brain, but also greater happiness in personal and social life. The better the two hemispheres work together the richer everything we do will be.

Susan Mayclin Stephenson, AMI Montessori 0-3, 3-6, 6-12 diplomas; www.susanart.net

|